Deep inside Essar’s sprawling oil refinery on the banks of the river Mersey, a £200mn machine smashes the molecules in crude oil to help produce millions of litres of diesel, petrol and jet fuel every day for the UK transport industry.

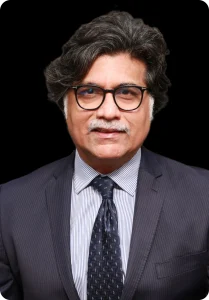

The catalytic cracker is the moneymaking engine of the Stanlow refinery. “Without this unit we’d make zero profit,” said Marcos Matijasevich, head of low-carbon transition at refinery owner Essar Oil. “You would have a really basic refinery.”

But it also contributes heavily to one of the site’s biggest problems, accounting for more than 40 per cent of its annual greenhouse gas emissions of about 2.1mn tonnes.

It is a figure Essar’s bosses want to bring down. If not, the refinery in Ellesmere Port, which produces 16 per cent of the UK’s road transport fuels, is likely to face increasingly big annual bills as the UK government tightens rules about using clean fuels and how polluters pay for their emissions.

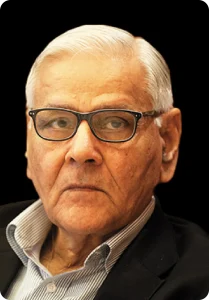

“Europe and the UK is quite a tough place to be, compared to other parts of the world, for lots of reasons,” said Tony Fountain, managing partner at Essar Energy Transition, a division set up by the refinery’s ultimate owner, India-based Essar Group.

“One of them is quite aggressive carbon regimes. To be viable in the future, we need to have a decarbonisation strategy.”

Stanlow’s challenges are shared by the UK’s five other large refineries, which are all under pressure to cut their carbon emissions. Over the longer term, they also face declining demand for their products as petrol and diesel cars are phased out in favour of electric vehicles.

Consultancy Wood Mackenzie expects demand for refined products to hold up in Europe at least until the end of the decade, while the sector globally has enjoyed record margins over the past year. But refinery owners must now work out how to put those profits to work to protect their future.

“We think for the rest of this decade the global [refining] industry’s OK,” said Alan Gelder, vice-president for refining at Wood Mackenzie, which expects oil demand to peak at 108mn barrels a day in 2032, up from almost 100mn b/d in 2022. “Then the risk of closure starts to emerge in the 2030s.”

Stanlow’s efforts are focused on carbon capture and hydrogen: it aims to strip out carbon emissions from critical processes such as catalytic cracking and it is also planning to produce hydrogen at the plant, extracting it from natural gas.

Under its plans, which are still at an early stage, emissions from both processes would then be piped out to Liverpool Bay and stashed in depleted gasfields. The resulting “blue” hydrogen would be used on site, while Essar ultimately wants to also sell it to factories and other heavy industries in the UK. Last year, it bought a new furnace — used by refineries in the crude oil distillation process — that can be switched to work on hydrogen power.

“The thrust is [ . . .] to create a really leading hydrogen business,” said Fountain. However, future demand for hydrogen, which has been proposed as a source of low-carbon energy for everything from heavy industry to homes, is highly uncertain. Production costs are high and new infrastructure and equipment would be required.

EET Hydrogen, the Essar company that is planning to build the manufacturing plant at Stanlow alongside clean energy specialist Progressive Energy, has provisionally agreed to sell hydrogen to glassmaker Encirc. It has earlier-stage agreements with several other companies including glassmaker Pilkington but these are not yet firm sales deals.

Fountain estimates there could be demand in the region around Stanlow to support 4.5GW of hydrogen production towards the end of the decade, based on current plans and government targets. This is almost double the UK’s current production capacity.

He also rejected the idea that blue hydrogen made using natural gas and carbon capture will struggle to compete with green hydrogen made from water in a process powered by cheap renewable electricity.

“I am not sure that’s true in the UK,” he said, though he added that cheap solar power in India could enable “very economic green hydrogen”. Essar also plans to develop a new import terminal in Liverpool for “green” ammonia, made using renewable power, which can then be converted back into hydrogen. Some of this could come from its own projects in India.

Essar has said it wants to invest $2.4bn in the UK, but its hydrogen plans depend on state support. EET Hydrogen is in talks with the UK government about a contract to support revenues from the planned new hydrogen plant, as part of wider measures to help the nascent industry compete with natural gas. “At the moment, burning natural gas and buying carbon allowances is still cheaper than buying hydrogen,” said Matijasevich.

Low-carbon hydrogen production features heavily in other UK refinery decarbonisation plans, although some have run into problems because of costs and lack of infrastructure.

US company Phillips 66 and Danish wind developer Ørsted decided in the summer to “pause” their “Gigastack” project, which would involve making hydrogen from water with power generated by wind farms in the North Sea and using it at Phillips 66’s Humber refinery in the east of England, as well as selling it to other industries.

The two companies have withdrawn the project from a government funding round, saying that “further project maturation together with supply chain development is required”.

Meanwhile, chemicals group Ineos suspended work on a £350mn hydrogen-ready heat and power plant at its Grangemouth refinery and chemicals site in April 2022, citing spiralling costs, and has yet to resume. The plant is one part of its plan to cut the site’s roughly 3mn tonnes of annual carbon dioxide emissions.

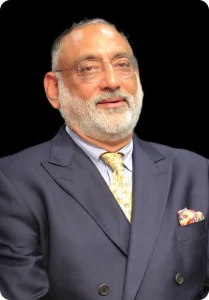

Ineos’s and Essar’s plans also rely on supplies of reasonably priced natural gas, from which to extract the hydrogen. Andrew Gardner, chair of Ineos Grangemouth, said that the Labour opposition’s plans to stop new exploration licences in the North Sea if it wins power could increase reliance on imports.

He stressed Ineos is committed to decarbonising, with a target of net zero carbon emissions at Grangemouth by 2045, even after falls in the price of carbon permits cut costs for polluting industries.

“If you did it only on the carbon price then you’ve missed the point,” he said. “It’s about the planet. it’s about having a licence to carry on.”

While industry experts do not expect all of the UK’s refineries to stay the course, Essar is optimistic. “I think the way that [our decarbonisation] strategy plays is, it will help us be the winner in a very long end game of fuels,” said Fountain. “Not every refinery will survive . . . there’s a bit of last man standing.”

Source: Financial Times