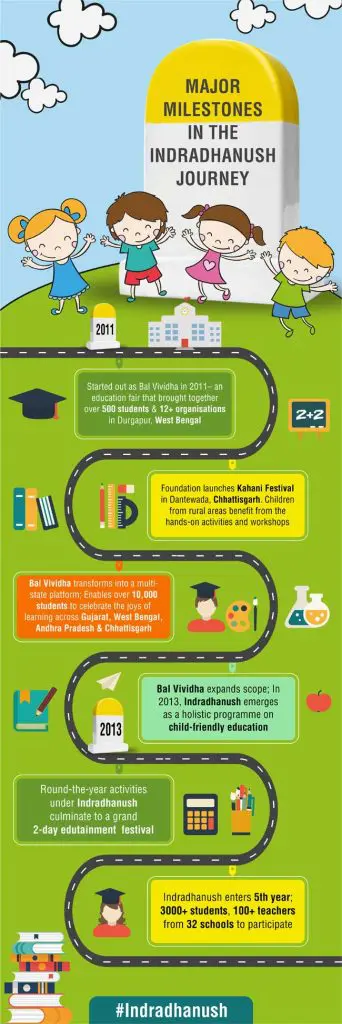

There are few occasions in India when children, irrespective of their age or social status or what part of India they live in, can truly just be children. Now there’s an exception: Indradhanush, a two-day annual event in Jamnagar, in the state of Gujarat, India, that takes place in February. It’s a programme specifically designed for schoolchildren aged 9 to 14 that is organised by the Essar Foundation, part of the Essar Group, India’s fourth largest company. Indradhanush means “rainbow” in English. This year, it was attended by over 3,000 students and close to 100 teachers from 32 schools from surrounding villages.

The Foundation organises Indradhanush in collaboration with the Centre for Environment Education, with a focus on enabling young minds to learn in different ways. This year’s theme was astronomy and local biodiversity. Speakers selected for the event were invited not just for their knowledge, but for their ability to be able to engage with children – they had to be riveting storytellers, as well.

The topics of local biodiversity and astronomy were brought to life through the exhibits and models, and from interactive activities that included educational games, puppetry and sing-alongs. The mobile planetarium, a screening of a 3D film and the launch of a rocket – all were hugely popular. It is safe to say that all the children who attended Indradhanush would have never had experienced anything like this before, because they come from poor village schools with very limited resources.

Deepak Arora, CEO of the Essar Foundation, is behind this ambitious event. “Indradhanush is about children coming together to learn,” he explains. “To have an enjoyable experience that goes beyond the classroom. The idea is to have the event jam-packed with activities that engage the children, make them laugh. Then we know if we have succeeded in what we have set out to do. There was definitely lots of laughter – that means Indradhanush was a success.”

ENROLMENT

Programs like Indradhanush contribute to a strong education system, the cornerstone of any country’s growth and prosperity.

Over the last decade, India has made great strides in strengthening its primary education system. The District Information System for Education reported in 2012 that 95 percent of India’s rural populations are within a kilometer of a primary school. The 2011 Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), which tracks trends in rural education, showed that enrolment rates among primary-school-aged children were about 93 percent, with little difference by gender.

However, behind such promising statistics, the records about current learning show much room for improvement. The 2011 ASER stated that only 48 percent of students in the fifth grade could read at second grade level, while the number of students completing their primary education with inadequate numeracy and literacy skills is startlingly high.

The majority of Indian children attend government-run primary schools in rural areas. In 2008-2009, rural India accounted for more than 88 percent of India’s primary-school students, over 87 percent of whom were enrolled in government-run schools. This is where we see some of the country’s toughest challenges.

The quality of teaching is a large issue. Teachers working in primary schools across rural India have a difficult job: teaching multiple grades, with textbooks that are pitched far above the comprehension level of students and in classrooms that have children with different levels of learning achievements. Plus, many teachers themselves have relatively low educational qualifications; in 2008-2009, on average, 45 percent of these teachers had not studied beyond the 12th grade.

Low levels of teacher motivation also affect the quality of primary education. Twenty-five percent of primary-school teachers in rural India were absent on any given day in 2002-2003. The impact of absenteeism is aggravated by the fact that the average primary school in India has a workforce of no more than three teachers.

Another disheartening element is a highly bureaucratic administrative system that discourages decision-making and makes implementation difficult. Plus, India’s linguistic diversity creates unique challenges for the nation’s education system as the country’s 22 official languages and hundreds of spoken dialects often differ considerably from the official language of the state or region.

Students with rural primary schooling are at a significant disadvantage as they transition to higher education, because India’s best universities teach exclusively in English. Part of the problem is that when teachers themselves know little English, especially spoken English, how will the students learn?

Another issue is that rote learning has been institutionalised as a teaching method. Primary school teachers in rural India often educate students by making them repeat sections of text over and over again. The result can be stunted reading comprehension skills. For example, students in grades two and three in some schools struggle to read individual words, but can neatly copy entire paragraphs from their textbooks into their notebooks.

EFFECTIVE

Reports show that India’s children are not achieving class-appropriate learning levels. This is why initiatives like Indradhanush are so relevant. The programme encourages not just improved learning, but also requires teachers to be accountable. It shows primary school teachers what effective education for young children can look like. Interactive, dramatic, taught with aids besides textbooks, Indradhanush makes learning fun – and effective. It’s a model for an Indian national education system that needs inspiring examples.

India’s economic growth story remains one of the most anticipated global economic trends. The current lag in India’s productivity growth rate, which trails behind other East Asian economies, could be attributed, in part, to deficiencies in the national basic educational system. Improving education at the primary school level is a critical area of investment if the country wants to increase prosperity in coming years. Properly educating the country’s youngest generation will produce the smart, skilled, well-schooled workforce of the future.

– By Sangeeta Haindl in Ethical Performance Journal.

This article appeared in the April, 2016 edition of Ethical Performance Journal. For more such stories, log on to www.ethicalperformance.com